Opinion On March 9th, Apple had its spring reveal. The stars of the show were a nice monitor, a new budget iPhone, and the Mac Studio, a Mac Mini stretched in Photoshop. Reaction was muted. There'd been some very accurate pre-launch leaks, sure, but nobody had cared about those either.

If you're over five years old, you'll remember when pre-launch leaks didn't happen, while plausible fakes caused more buzz than John McAfee's stash of speed.

We all have gadget fatigue, we all have other things on our minds.

Yet the actual tech within the Mac Studio is genuinely breathtaking, not because Apple has rewritten the rulebook, but because it's the clearest marker yet of how extreme small personal computers have become. Youshould be amazed. You should be talking about nothing else. You're not. We have a problem.

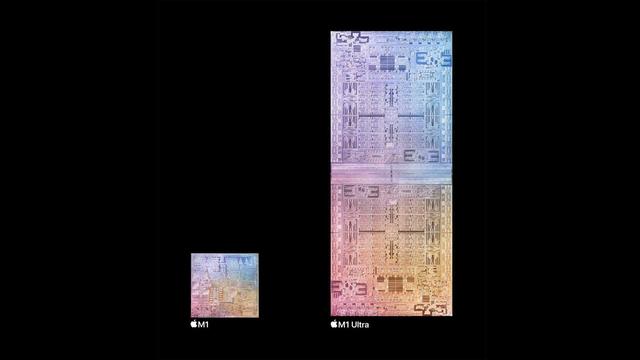

Take some raw numbers. The Mac Studio Ultra starts at $4k. It weighs about 4 kilograms. It has a 400 watt power supply. It can clock up around 20 TFLOPS – twenty million million floating point operations a second, if you're feeling blasé – thanks to its M1 Ultra SoC, one of the highest performing devices in mainstream computing.

The Mac Studio Ultra is vastly superior to the world's fastest supercomputer from 2001, IBM's one-off ASCI White. That cost $170m, weighed over 100,000 kilograms, took six megawatts in processing and cooling, and produced a paltry 12 TFLOPS.

Do the sums to combine everything that's better in FLOPS per kilo per watt per dollar, and the Mac Studio Ultra is twenty million million times ahead of ASCI White. Plus you can buy it online, it runs Netflix, and it's too small for your cat to sit on.

It's true that the M1 Ultra chip, for all Apple's fanfare, isn't the fastest general purpose CPU you can buy, and is even further behind the buffest GPU cards. Nonetheless, you can outperform the biggest computer in the world from a couple of decades ago, twice over, in your living room. You probably won't bother. If you don't care, why should anyone? That's the problem.

If you've been in IT for most, all or more than the years between ASCI White and Mac Studio, ask yourself what, in 2001, you would have said if offered the chance to have the world's most powerful computer all to yourself.

Those were crazy days, my friend, days when each new generation of computer let you do something for the first time you could never do before. This was the time of insane momentum that had taken us from monochrome text to colour graphics to photo-quality, from single-note bleeps to CD quality sound editing, fromSpace Invaders to 3D gaming, from tape to gigabyte drives, from downloads barely faster than typing to video – but not TV-quality streaming, YouTube was still some years away.

All that, and the Web was just getting going. Oh. My. Gawd. What next?

If you were a developer – "programmer" in the Old Tongue – or had other scientific or technical interests in computation, then it was even better. The regular leaps in performance and potential kept your love for the field alive. Your code magically ran faster, your data could grow ever bigger, your UIs become ever more gorgeous, and you just had to sit back and let it happen. You could even see what next might be like.

Above it all, the stratospheric mysteries of supercomputing hung like the PCs the gods themselves ordered from the Mount Olympus edition of Byte. Supercomputers were 20 years ahead again, but they'd be with us mere mortals if we just stuck around.

We didn't know it back then, but Gen X were being both pleasured and spoiled by growing up alongside Moore's Law, and got to see the digitisation of global culture and technology happen at first hand.

It was easy to be in love with IT; if you had the geek gene, impossible to avoid. Now, even for those who lived those years and are habituated in our expectations and interests, the automatic magic has gone. Every two years used to bring a wow moment when tech gave you something new. You'll remember your first, and your second, and your third. Can you remember your last?

This would be so much bah-millennials old fartism if the industry didn't have such a tearing need for new blood, and the constant infusion of people engaged, enthusiastic and eager to put in the work for intellectual rewards. This isn't a new observation. It's what led to the invention of the Raspberry Pi 10 years ago, making something cheap, open and capable of regenerating those wow moments by stripping away the crud of commercial computing. That only goes so far, though. It works if you're not put off by naked PCBs, and most are. It doesn't solve the other huge demographic brake on fresh ideas in tech, the lack of diversity.

Look again at our desktop supercomputer. It's still producing wow moments, but they're focused in areas that still seem magic to their practitioners. Like the supercomputers always have, it earns its spurs modelling realities. Graphics mavens scan and sculpt, build and tinker, with instant gratification. Developers build and deploy ideas in minutes from components and tools that would have taken months of teamwork. Astronomers make and explore galaxies.

What the personal supercomputer has become is a divinely powerful construction set for ideas in any medium, technical and artistic, but only for the skilled and the experienced. You have to push it: golden age IT pulled you along behind it, if you just had the wit to hold on.

Serving up wow has to be a top priority. Where is the IT chemistry set? Where is the Build Your Own Cosmos for ages 7-11? Where is the Fisher-Price digital audio workstation? Where, in short, is the Toys-R-Us of the digital world? Our computers, our networks and our tools are more than good enough to offer anyone of any genre, any age, geek or normcore, a wow reward for creative engagement. We are twenty million million times better at computers now than 20 years ago: it's time we cashed in some of those chips to earn the love of the next generation. ®