Anniversaries are moments for reflection.

So what is the story of the past two years?

It’s a story of loss — 964,000 dead (and counting) nationwide; 812 in San Francisco County; 1,792 in Alameda. It’s also the story of learning new ways of being — something we’re doing once again as pandemic-era restrictions are lifted and we allow ourselves some cautious hope.

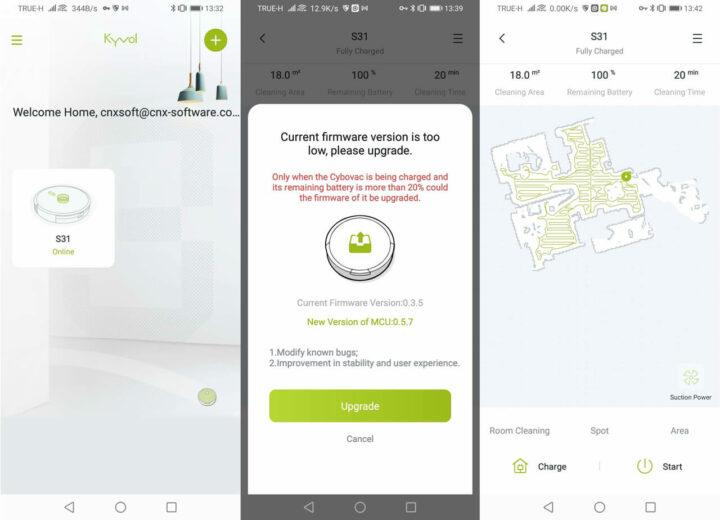

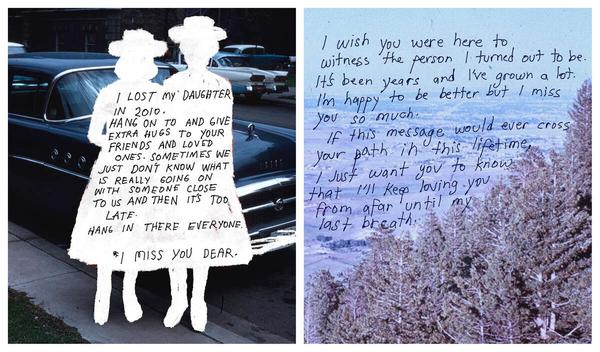

About a month and a half before the call to shelter in place, Geloy Concepcion, a photographer living in El Sobrante, posted a picture to his Instagram. The image is overexposed on one side; on the other you can make out cars driving across a bridge under a purple-fog sky. At the top, in big, all-caps print, Concepcion had written a confession of sorts: “I wish I can say it all in English, so I won’t have to pretend I don’t know shit!”

Concepcion had moved to the Bay Area from the Philippines in November 2017 — a day after his wife gave birth to their daughter, Narra. It was a chance to “start fresh.” But for two years, he had to put his career as a photojournalist on hold while he waited for a work permit. During those years, his world became smaller — most of his time was spent taking care of his daughter — and his images became more intimate; the small child sleeping, the berries he had prepared for her. When he finally received his permit, he sent out a flurry of pitches to photo editors.

“I was really hyped up to work,” he says. When he didn’t hear back, he began to feel like a failure.

That’s when he came across an old folder of film photos and decided to ask others about the things “they wanted to say but never did” and then scrawl what they told him across the images.

He couldn’t have known, of course, that a pandemic would soon send everyone indoors, searching however they could for connection, and yet his project was almost perfectly timed. He’d started making the pieces because “I was already isolated” and now others were, too.

As his work spread across the internet, he began to receive about 1,000 notes a week from around the world. A project born of isolation led to 434,000 followers online, and as they looked at Concepcion’s pieces, they began to notice his other work as well. He said it became “the only thing that connected me to the world.”

When Navneet Arora thinks about the past two years, he can’t help but marvel at “the resilience of mankind.” Arora is the chief people officer for Roofstock, an Oakland-based financial technology company.

During the past two years, the company has learned how to operate remotely. Not long ago, he never would have imagined hiring somebody over Zoom.

“We’ve had a paradigm shift,” he says. “We can be productive, we can build relationships without having met them.”

Now he can’t imagine going back to a world the way it was. The company has slowly begun to reopen its Oakland offices on a volunteer basis, but their future is hybrid, he says.

“I don’t think any of us could have foreseen what was coming and how well we adapted to it.”

As restrictions lift and case counts drop, we’re being asked to adapt again, to a world where this coronavirus is treated as endemic. For as long as we have been waiting for a return to normalcy, this transition hasn’t been easy. There have been too many false starts to be entirely optimistic about the future. Maya Johannson, CEO of Well Clinic, a mental health care provider, describes it “as being scared to be hopeful.”

“We were kind of here last summer a little bit,” she says. Her patients talk about the ebb and flow of optimism and despair.

Moving on will require a certain force of will, she says.

“We’re habituated to really isolating routines. … It’s the easiest path. We’re going to need to muster up some collective grit to get back to a normal that involves more in-person interaction.”

Bit by bit, that’s happened.

One day during the pandemic, Brittany Newell, a San Francisco writer, noticed that she had stopped listening to music. Music reminded her of a vibrant world, one where she could go dance at Aunt Charlie’s (a divey, old-school drag bar in the Tenderloin), any night of the week. “It would make me too sad.”

For two years, she turned inward, “a move toward introspection in ways that are both good and not good,” but recently that changed: “I feel this old impulsiveness or restlessness.”

Lately, Newell has been throwing parties (“Juicy Fruit”) at a new bar in the Mission District. Last month it was packed, and she danced for the crowd, pulling dollar bills out of waving hands.

“It felt so good. It felt so exciting,” she says. “I feel cautiously optimistic.”

The memories of a summer cut short keep her grounded — “I do feel hopeful, but it’s a little bit one more day at a time.”

For others, normal is a ways off. Kimia Rahnemoon gave birth to twin daughters 4 ½ months before shelter in place.

In those early months, Rahnemoon would take her daughters to the park almost every day to lie in the sunshine.

Then, suddenly, parks and playgrounds were closed.

Now, even as the world opens again, she and her husband, Farrid Hosseini, have tended toward caution: “They don’t even know shopping in person is a thing.”

They’re waiting until the day their daughters are cleared to be vaccinated.

Until then, Rahnemoon stays home with her daughters, her professional life on pause.

She’d expected to take six months off, maybe a year, to take care of her daughters — it’s now been nearly 2 ½ years since she’s worked in management consulting.

And she can’t help but wonder what these two years will mean for her children as they get older: “They will definitely have experienced some of these life-altering experiences — who knows how that might play out in their lives.”

Catalina Do, a senior at an East Bay high school, knows all about the difficulties of adjustment; she’s spent two years navigating changes.

“We had this whole year of going to online school,” Do says. “Fast forward a year, we have to adjust to something else, new procedures and new rules.”

School might be back in the classroom, but it’s a stripped-down version of what Do imagined her senior year would be — there will be a prom and a graduation ceremony, but all the other usual events have been canceled.

“I feel like I’ve missed out on a lot,” she laments.

Still, none of this has stopped her from imagining a future.

It’s college application season, and she’s waiting to hear back. Her top two choices are UCSF and UC Berkeley. She plans to study molecular biology, so she can one day be a pediatric oncologist.

If anything, she says, the pandemic only made her more determined. “I’m just excited to leave this bittersweet feeling behind and start a new adventure.”

During the past two years, Concepcion has made dozens and dozens of pieces for his project about things left unsaid. Over time they change. In his most recent work, which uses found and donated images, he creates a white space where the people once were, adding another layer of melancholy.

The notes he chose weren’t necessarily related to the pandemic, but it’s hard not to read them in that light.

Funny thing about death is it reminds us to live.

I find myself grieving over the person I used to be.

I feel trapped in my own life.

And yet, the project, at its core, is one of connection and the letting go of burdens — and something interesting happened during the course of this project and the course of the pandemic.

“I learned from it that our work can be deeper beyond our physical jobs,” Concepcion says.

Basically, he came to understand that photography was simply a medium. Deep down, all he’d wanted was to share stories.

As a general rule, we don’t get to choose how we learn life’s lessons, and here the pandemic offered him a salient one: “You have to find your purpose, your vision.”