JADC2 Puts Pentagon Under Pressure to Revamp Satellite Comms

3/17/2022By Meredith RoatenDefense Dept. illustration

Service leaders have been consumed with department-wide efforts to connect sensors and shooters and achieve information dominance at the tactical edge known as joint all-domain command and control.

But their goals could be stymied if the Space Force and other agencies can’t transform today’s satellite communication architectures, experts say.

The Space Force, alongside other space agencies, is evaluating how it can reconfigure its complex structure of satellites to build a more reliable and advanced network. This restructure of satcom and other space systems is expected to help lay the groundwork for JADC2.

Service officials say they are prioritizing building a space architecture that can withstand great power competition. Chief of Space Operations Gen. John “Jay” Raymond said the 2023 budget request will reflect that focus.

However, the service, alongside other space agencies, has faced obstacles. Challenges emerged as the service embarked on a redesign of its architecture because legacy systems must continue to operate as they are upgraded, Raymond noted.

“We’ve had to come up with this bridging strategy,” he said during an event hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “We have in our work come up with the right mix of being able to manage risk as we transform.”

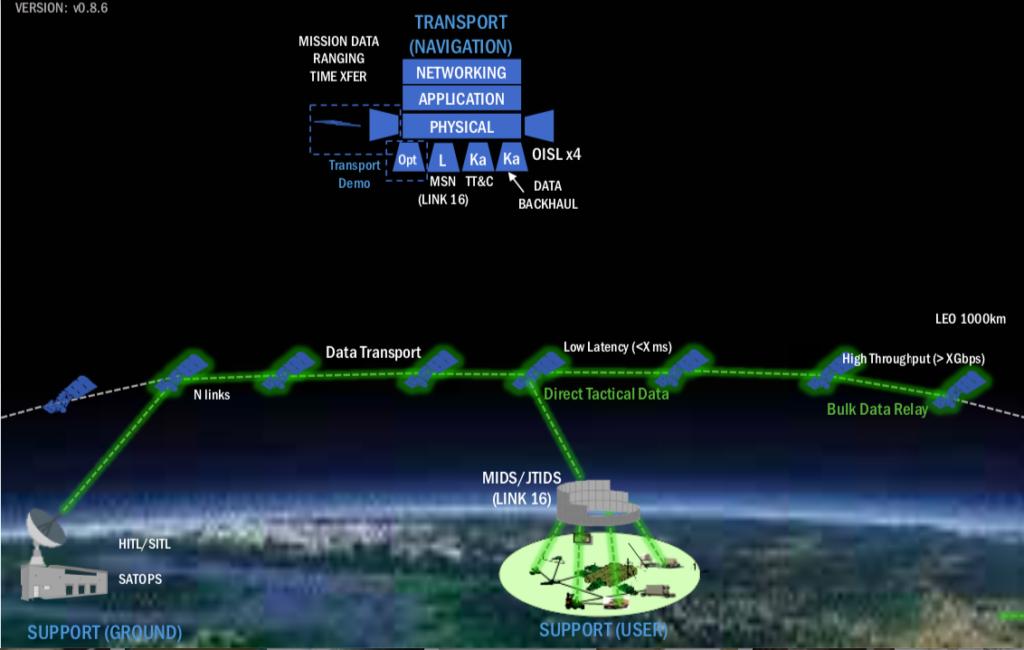

The redesign of the data transport layer — which includes a plan for a constellation of low-Earth orbit satellites that will provide connectivity for 95 percent of the world — will be a key part of achieving the Pentagon’s joint all-domain command and control mission, Raymond said.

The military’s current space architecture is outdated and puts the United States in danger of falling behind Russian and Chinese space threats, according to a recently released report from the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies titled, “The Backbone of JADC2: Satellite Communications for Information Age Warfare.”

The study urges the military to modernize its communications satellites to keep pace with Russia and China.

Increasingly, adversaries’ military doctrine focuses on how to contest U.S. space operations, according to the report.

“Both the People’s Liberation Army … and the Russian armed forces regard U.S. information flows to, from, and within space as high priority targets against which they are developing and deploying multiple attack options,” the report said.

Beijing relies heavily on its access to the space domain. Technologies such as space-based remote sensing and precise positioning, navigation and timing data are key capabilities that underpin its strategy, the study noted.

Additionally, Moscow’s portfolio of anti-space weapons includes jammers, directed energy weapons and ground-based anti-satellite missiles, the report said.

Despite this investment from adversarial nations, the United States has left its satellite communications architecture largely vulnerable and susceptible to attack, said Kevin Chilton, co-author of the report and an expert at the Mitchell Institute’s Spacepower Advantage Research Center.

The Pentagon has been accustomed to assuming access to satellites is assured, he said during the Mitchell Institute’s rollout event for the policy paper.

“Space is not a sanctuary,” he said. “Our satcom systems must be more resilient and agile if they are to provide the secure, on-demand connectivity required by our warfighters.”

There is already evidence of the U.S. military falling behind, said Lukas Autenried, a senior analyst at the Mitchell Institute.

For example, during the 2021 exercise for the Army’s Project Convergence initiative — which tests out technologies in support of JADC2 — next-generation systems struggled to process all the data necessary for them to operate, Autenried said.

Meanwhile, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance systems produce so much data that there isn’t enough bandwidth to move the information efficiently to decision makers, he noted.

“You really have both a supply and demand problem in terms of moving information from where it is to where it needs to get to,” he said.

Additionally, there are drawbacks associated with the current architecture when it comes to the size of individual satellites and the number of spacecraft on orbit, according to the report.

Individual systems have become larger in size and consequently more expensive, Chilton said. For example, the current generation of satellite constellations averages about $1 billion per spacecraft acquisition, according to the report.

U.S. military communication satellites cover about 42 percent of the world with a core of about 36 space systems. Most of them are located in geostationary orbit, or GEO, and the reliance on such a small number could mean critical outages if even a few are taken out in an attack, the study noted.

“While our satcom architecture is extremely efficient, it is also brittle,” Chilton said.

David Voss, director of the Spectrum Warfare Center of Excellence at the Space Warfighting Analysis Center — one of the organizations working on developing a hybrid design for the U.S. space architecture — said the solution “can’t come soon enough.”

Despite the urgency, it is taking a long time to analyze how different satellite configurations would integrate and meet all the needs for the services and organizations that rely on the technologies, he noted.

“It will be a work in progress for a while,” he said. However, “we can’t wait years to do analytics and make decisions.”

There are several configurations the center is considering for the future space architecture, Voss said. For example, it is weighing the cost of an entirely new terminal owned by the Space Force that would be able to roam across different layers of satellites.

“From a Space Force standpoint, we really want to be very cognizant and aware of the implication of the orbital deployment strategy to the user hardware going forward,” Voss said.

While he acknowledged a diverse array of satellites will prevent an offensive attack from taking out too many satellites at once, he emphasized the need for more analysis to determine how to leverage the strategy without it being cost prohibitive for the services.

A hybrid architecture means positioning satellites in different orbits around the Earth. While most communication satellites are in GEO, more spacecraft need to be deployed in low-Earth orbit, or LEO, and medium-Earth orbit, or MEO, according to the report.

One advantage of LEO and MEO is that satellites that are closer to the ground provide lower latency compared to those in geostationary orbit.

“It takes a lot less time to send a signal a few 100 kilometers up to LEO than 32,000 kilometers up to GEO because light travels through the vacuum of space faster than the glass inside fiber optic cables,” Autenried explained.

This will be crucial to positioning the military for future fights, he said. For example, capabilities such as time-sensitive targeting, advanced heads-up displays and autonomous systems rely on real-time data to operate.

Last April, the Space Development Agency announced plans to have the first constellation of tracking and communications satellites, known as Tranche 0, in low-Earth orbit by the end of 2022. The organization’s plans call for launching a new tranche of satellites every two years.

However, putting new satellites into orbit won’t be simple. For JADC2 to work, the systems will need to be interoperable, Autenried said.

“Network interoperability is going to be absolutely critical to enabling disparate joint systems to interact effectively,” he said. “That’s just simply not the case today.”

The Pentagon over the past two decades has also relied heavily on leasing capacity from the commercial satellite industry to take up slack when military satellites are overcapacity. Many satellite communication innovations have emerged from commercial providers and the military should leverage this new technology, the report said.

One organization that is making progress is the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, according to Stephen Forbes, program manager for Blackjack, which is the agency’s effort to bring commercial industry technology into low-Earth orbit satellites for the military.

The agency plans to launch as many as 12 satellites into low-Earth orbit by 2022.

Industry has eagerly responded to Blackjack because operating in the lower orbit makes low-cost payloads viable, Forbes said.

“We essentially got daily offerings across the full spectrum of space remote sensing communications, and [positioning, navigation and timing] that were all viable,” he said.

The program has now awarded 13 payload contracts across different mission areas including communications and missile tracking, he said. Companies are still undergoing design review and other evaluation, he noted.

Putting satellites in low-Earth orbit can help siphon only the essential data from a gargantuan information stream, Forbes said. It will enable leaders to continue to use capabilities that produce large volumes of data without burying them in it, he said.

Low-Earth orbit is also ideal because the radiation levels found in other orbits puts stress on the processing technology needed to sort out useful data, he explained.

“It allows you to essentially decimate that data and get the key information attributes out of that data stream and just disseminate those,” he said.

One of the satellite technologies DARPA is testing is laser communications.

With this capability, an optical terminal sends data through space with a low-power laser beam.

Lasers operate in much shorter wavelengths compared to radio frequencies. The Mitchell Institute report compared the upgrade in data transfer rates to switching from a dial-up modem to broadband internet. The concentrated signal from the laser used for optical communications means hardware can be smaller and employ less energy than radio frequency, Autenried explained.

“These sort of size and power consumption considerations are particularly important when you’re talking about space where both those things are going to be an absolute premium,” he said.

Lasers are much harder to disrupt with a jamming attack compared to radio frequency, he said.

One application for optical communications is for satellite crosslinks, which would enable spacecraft to talk to each other without using a computer on the ground as a go-between, according to the report.

However, “the ground infrastructure they need to support these constellations would be enormous and it also adds a stupid amount of complexity and timing in terms of trying to get information from where it is to where it needs to be,” he said.

Forbes said the Blackjack project will try to show the potential of optical networks for communication satellites.

“The ability to stitch [satellites] all together in a resilient mesh is going to be a critical enabler to overcome the threats and the challenges that we face and build a much less brittle architecture,” he said.

Meanwhile, the industrial base will be challenged to meet the demand for new satellites, according to the report.

“Launching constellations consisting of hundreds or even thousands of satellites within a few years requires satellites to be manufactured at an unprecedented rate for the space industry,” the document said.

Satellite manufacturing is labor intensive and involves lengthy quality assurance methods, according to the report. New manufacturing techniques such as 3D printing or automated production should be integrated into the process to streamline it, it suggested.

Topics: Space