Nothing strikes terror into the heart of California residents more than three words; ‘The Big One’. This, of course, is referring to the fabled earthquake that will strike with such magnitude that some experts predict everything west of the San Andreas fault line will drop into the Pacific Ocean. Ironically though, it’s often joked that the owners of the modest suburban homes just east of the fault line can’t wait for this to happen. Overnight, they would become multi-millionaires thanks to the newly formed coastline that their relocated ‘beach front’ homes would overlook.

On average, the Golden State experiences over 10,000 earthquakes per year, but most are not felt and only picked up by the most sensitive of seismographic devices. However, out of that mind-blowingly high number, only between 15 and 20 events are of a magnitude of 4.0 and above; the level at which serious structural damage can start to occur.

It’s not surprising that earthquake damage prevention regulations feature high on the list of California state building codes. These codes first came into force following the great earthquake of 1906, where some 3,000 San Francisco residents lost their lives and about half of the population were left homeless. Since then, regulation has constantly been updated to take into account of new advances in earthquake safety technology.

In days gone by, many buildings were lost, not directly because of the actual seismic motion, but from the resulting fires that followed. These were often fed by the abundance of escaped gas through ruptured gas lines. Since 2000, by law, all newly constructed homes have to be fitted with what are known as ‘seismic natural gas shut-off valves’. This move was followed by individual counties making it compulsory to retrofit these devices into existing homes, in line with growing insurance policy stipulations.

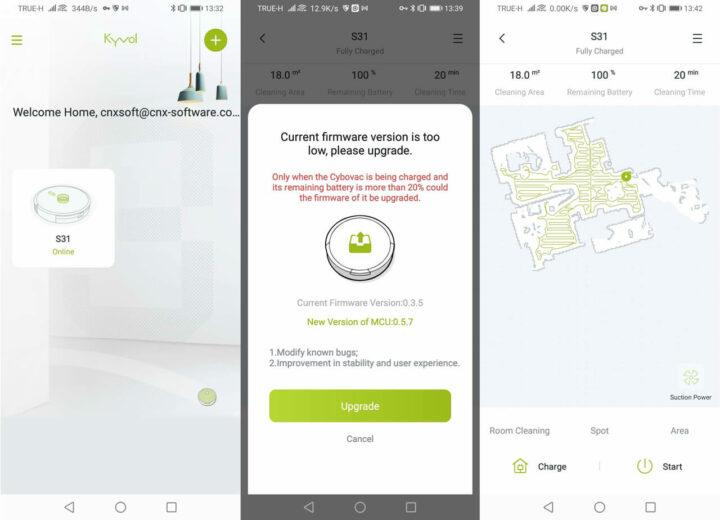

While there are various approved models available, arguably the market leader is aptly named the ‘Little Firefighter’. Being a registered Gas Safe Engineer myself, I take a particular interest in anything gas related, and I recall the first time one of these was pointed out to me. My initial reaction was that I was looking at some old Honeywell gas valve that had somehow had the controls and solenoid blanked off with flat pieces of aluminium (main image).

This relatively tired looking device was installed just downstream of the meter on the consumer pipework. When it was explained what I was looking at, curiosity got the better of me and I wanted to know what wizardry was contained within it. Looking at the body of the valve, it seemed very basic, almost primitive, and was certainly not what I expected of something branded with the impressive description of ‘seismic natural gas shut-off valve’.

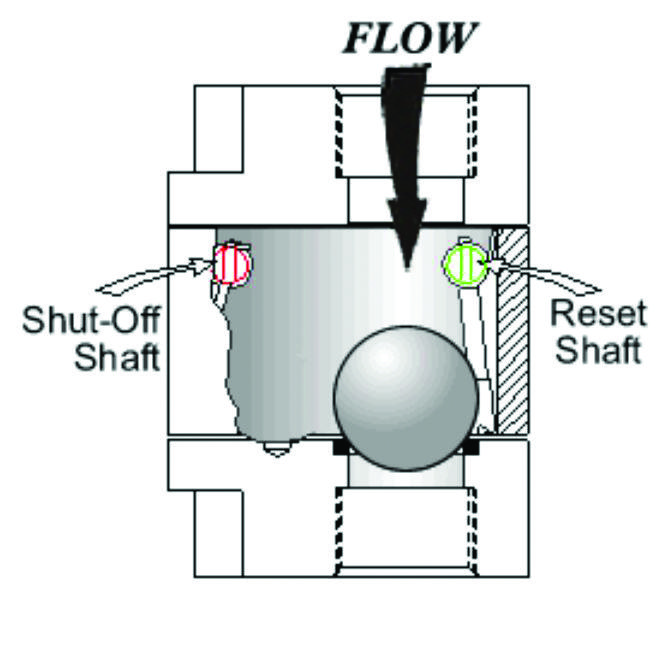

I naturally assumed that the device would feature some sort of smart solenoid that would snap close in the event of shaking, but clearly this wasn’t the case, as indicated by the lack of wiring. Instead, inside is the most basic of mechanisms. Inside the body there is a steel ball of about 1” diameter that is retained almost precariously on a slightly raised, horizontal ring. This ball sits by the side of the gas flow channel. When movement occurs, the ball simply wobbles off the ring and drops onto a seating in the outlet to the downstream pipework, stopping the flow (diagrams – below). In this day and age of electronic sensors, valves, and other state-of-the-art gadgetry, the lack of complexity is almost refreshing.

The device is infinitely resettable over its approved 40 year lifespan. However, if it is activated (set to operate during a quake of 5.4 magnitude or above), it’s strongly advised that a qualified professional checks the integrity of the pipework, both in and around the property before reinstatement of the gas supply.

The way in which the device is reset is as simple as the way it operates. In the side of the aluminium body are two slotted screw heads. These in turn connect directly to two internal paddles either side of the steel ball, one to knock the ball back into its armed position on the ring (reset), the other to knock the ball onto the seating to seal the supply (test).

In addition to the seismic shut-off valves, some California counties do permit the use of full flow valves that utilise a spring-retained cone that seals into a corresponding housing. These operate when gas flows abnormally high, although in the case of many earthquake-related gas line fractures, the escape might not be sufficient enough to activate the valve.

One thing that did make me chuckle though was being told by an HVAC guy that these valves often fall victim to the neighbourhood jokers with too much time on their hands – one swift kick and the homeowner’s shower goes cold midstream!