How smart is your “smart home” when it’s out of power?

Three years ago one of the biggest home builders in the United States created a show “home of the future” for CES, the Consumer Electronics Show. One of its big features: a receiving unit for packages delivered via drone on the roof, and another on ground level where a ground-based autonomous delivery vehicle could drop off a package.

Then Covid hit.

And the company had no idea how prescient they had been, as the pandemic more than doubled home meal deliveries.

But it suggests an interesting question: what makes a smart home smart? And why can’t we build our homes smart instead of trying to make them smart-ish, piece by piece, after the fact? Of course, the first question has many answers. The second, however, is just a matter of intention and will.

A perhaps even-more-important question: how can we make smart homes sustainable? Good for the environment, and good for the humans inside them?

“The word smart has so many meanings to it, and it could contextually mean something very different to a gamer versus a 55 move-up who wants some simple things,” KB Home VP Dan Bridleman told me recently on the TechFirst podcast. “But to me, I think it just depends on hey, lifestyle. What do you want? And how smart do you want it to be?”

MORE FROMFORBES ADVISORBest Business Credit Cards Of September 2021

ByDia AdamsEditorBest Crypto Exchanges For 2021

ByTaylor TepperForbes Advisor StaffExactly: how smart do you want it to be?

For some, a smart house is chock-full of gadgets that automate or monitor almost every conceivable part of a house. For others, a smart house is extreme simplicity with only the slightest of technological intrusions as necessity demands.

However, you define it, smart home is a massive and quick-growing market. Smart home was worth over $79 billion in 2020, and is growing at 25.3% per year, according to Mordor Intelligence. And it’s expected to hit $314 billion a year by 2026.

No shock: that’s partially impacted by Covid.

“The ‘new normal’ defined through the social distancing results in a requirement to go back to the redesign basics and reinvent the residential real estate product by factoring in new-age designing, efficiency, and innovation,” the research company says. “As the redesign happens, the need for a totally new set of amenities has resurfaced and gained prominence.”

KB Home has built 650,000 houses in the U.S. The company is on track to build a million soon, and Bridleman, as the SVP of technology, is tasked with making them smart.

But for Bridleman, making a home smart doesn’t start inside the four walls. It starts in the community.

“Bandwidth is key,” he says. “Being able to put fiber optics into a community at the very beginning, before you even start it, so that you can offer the appropriate bandwidth to be as smart as you want into a smart home.”

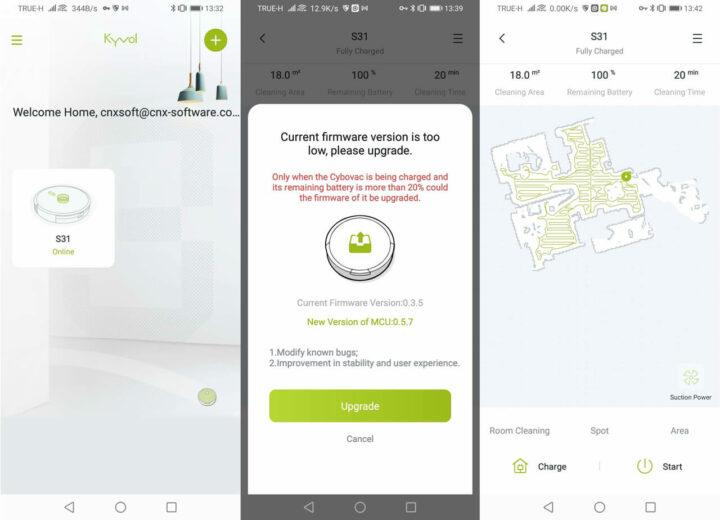

But there’s another important factor which hits ... home ... as I look at all the smart home apps on my personal phone: Apple’s Home app, Google’s Nest, Google’s Home app, Airthinx for one of my air quality monitors, myQ for my smart garage doors, Awair Home for another air quality monitor, an app for a smart bed, a Dyson app, a Wemo app, Nanoleaf, a Govee Home app ... and more.

Managing smart home is way too hard.

“You do need an ecosystem, fundamentally, because you can’t say, ‘Oh, here’s your brand new house, but oh, now you’ve got 300 apps with 300 passwords and you now need to connect them all up yourself, and you’ve got to figure out how all these things attach to your wireless network,’” Bridleman says.

That makes perfect sense.

And I wonder why Google or Amazon or Apple isn’t building Home Operating System to tie everything together. (Spoiler alert, Microsoft has a Home OS ... from 2010.) Each company has extensive smart home capability, of course, with Amazon probably in the lead, but they tend to focus on the ubiquity of a smartphone as the organizing principle in a smart home. (Amazon does have Alexa products that act us a hub; Google has the Nest Hub Max.)

Of course, it’s easier if you pick an ecosystem, of course, and stick to it. That would mean having an Amazon smart home, a Google smart home, or an Apple smart home.

Most don’t do that, and that’s a challenge.

Listen to the interview:

“What we need to do is we need to have that seamless integration where there’s a singular app that you can go to today — and today, that singular app could be something as simple as HomeKit or Amazon or whatever it is, because there’s not this one ecosystem that runs today,” says Bridleman.

What he’s focusing on, however, is building in intelligence from the ground up, not after the fact, and in only building in the intelligence that a client actually wants.

That's somewhat new.

Most of us live in homes that were build years if not decades ago, and we’ve layered in technology as it’s become available. That means Alexa might do our bidding or the door unlocks magically when we walk up, but it also means that some of the more futuristic promises of smart home tech — a roof that knows when it’s leaking, a window that dims hot direct sunlight but lets in cooler indirect light, or even a wall that knows it’s under too much strain — are much harder to install.

Such as, perhaps, a drone door for automated deliveries.

Or a kitchen that cooks for you.

Increasingly, however, what makes a home smart isn’t necessarily the Google Home on the shelf or the space heater with an app. It’s the fundamentals of what a home is supposed to provide: heat, light, shelter, power. Because lately our grid hasn’t seemed as stable as it has been in the past.

And that means solar, batteries, maybe even rainwater cisterns which all make us resilient to natural disasters.

“In California ... probably within the next three to five years it’ll be all electric,” Bridleman says. “We’re talking about what makes you smarter, but think about ... resiliency: what happens when the temperatures are 110 and there’s a Santa Ana, and the winds are coming 90 miles an hour through the canyons and electrical companies are shutting off grids because they don’t want to create a spark or a fire, and so you’re stuck without power ... you start to develop what’s called microgrids, where, through the use of solar on your roof, through the use of maybe battery backups in each house and battery backups at the community ... you can start to store that energy you’re producing during the day, use it at night, or in case of emergency, or use it to arbitrage energy rates as the energy costs [skyrocket] at seven o’clock at night.”

In other words, a smart house is one that does its job.

Even when your power provider doesn’t, or can’t.

And when a smart house incorporates solar, wind, geothermal, and energy storage, a smart house becomes a sustainable house as well.

That’s probably good news for the planet as well as for people who don’t want to halt their lives every time the grid shuts down. And it opens up very interesting possibilities for power sharing and distributed production for the future.

Subscribe to TechFirst, or get a transcript of our conversation.